In his Principles of Bibliographical Description, Fredson Bowers talks about how every bibliography has to have a unifying purpose in order to be something more than just a list of minutiae — or to borrow a phrase he borrowed, a “spire of meaning.” That sounds very elevated, very idyllic, to have a spire of meaning for your project. I have a hard time picturing Bowers as being fanciful, but his obvious attraction to the term “spire of meaning” goes a long way toward making that argument.

To the point, though, Bowers’ statement that a descriptive bibliography in particular cannot be simply a collection of raw facts about material books has a point. Like every fact or list thereof, a descriptive bibliography requires context and cohesion in order to make the data mean something. A collection without a theme is just material noise; it’s the order and context that give it meaning and transform it into a signal worth hearing. The same thing holds true for this project.

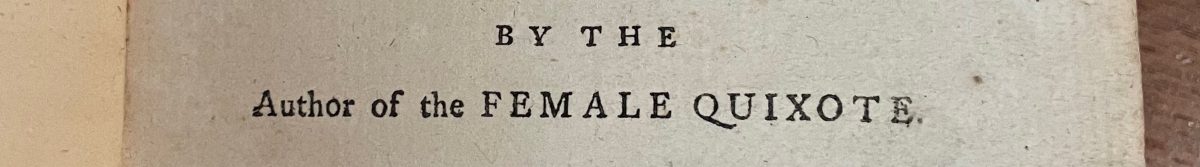

Now, while the foundational unifying principle for the Lennox Bibliography Project is in the name — a descriptive bibliography of the works of Charlotte Lennox, 1747-1850 — that’s more of a descriptor than a mission statement. All communication is edited; a perfect and complete transmission of knowledge is impossible, particularly in such a long-term effort at information gathering and presentation as this one. While it is currently a solo effort, it’s entirely possible that there will be collaborators down the line. It is crucial, therefore, to lay out not only the raison d’etre for the project, but also the rationales that guide our choices and determine how priorities are set and acted upon. Some of these are clear (and will be discussed in time); some are more challenging, and I have to define them as I go. One of the latter is the concept of feminist bibliography and how it relates to this project.

I am by no means the first scholar down this path. Sarah Werner is a leading voice in this field and has done a considerable amount of work, including some fantastic recorded talks, such as this one.

Kate Ozment’s article “Rationale for Feminist Bibliography” (Textual Criticism 13.1 2020) is pretty much required reading for why this approach matters and what forms it might take in application. It’s also open access and well worth your time, so if you haven’t looked at it, you should.

Margaret JM Ezell, Tia Blassingame, Lisa Maruca, Megan Peiser… all of these powerful scholars have engaged and are engaging with what it means to take feminism into a discipline so foundationally gendered as bibliography can be. It is only to be expected, then, that in a project like this one — focusing on a woman author, written by a woman scholar, with the hope of inspiring and facilitating the work of others in this vein — would have to come to terms with not only what a feminist approach entails, but what its ramifications are as a guiding principle. To take a page from others, then, I will lay out the following precepts.

Feminism for this project is defined as:

- Intersectional — it functions on the principle of inclusion, not exclusion. It is not exclusive to race, class, or gender identity.

- Transparent — by documenting this journey, its progress, and how decisions were made, it can serve as something between inspiration/object lesson for those who might be interested in doing something similar.

- Accessible — This bibliography will always be available to the public at large, at least if I have anything to say about it. There will be no charge to use it. It is an open resource.

- Political — choosing to carve a new path is inherently an act of resistance. The systems that led to an unbalanced representation and focus within bibliographical studies (among other things) are still there; it’s our participation and examination of how we got here and what really happens that makes change happen and keeps the discipline vital.

Feminist bibliography in praxis for the Lennox Bibliography Project is a work in progress, but here’s some building blocks to work with based on the above statements.

- The Lennox herself: It’s focused on Charlotte Lennox, who was a working woman writer who needed to support her husband, children, and herself.

- Bibliographical work is not — cannot — be limited to only “original” works. Lennox wrote plays based on existing material and translated numerous works. She collaborated and cultivated professional relationships of mutual benefit. A feminist bibliography cannot ignore all the nonstandard (but very common) types of work she did simply because she was not the sole original author of the material.

- Provenance is key, as is looking for copies in unexpected places and tracking how the copies came to be where they are. This is beyond the scope of most bibliographies and is something I’m still trying to figure out, but I feel like it’s an important piece of the puzzle and I want to find a way to include the data where I can.

- Open access and shared data sets. I want to make what I find available for others to use and replicate. I would dearly love to get an interface together that others could use with their data, but that’s almost an entire second project. We’ll see. I’ve got time.

- Elevating voices. I want to stay connected with others doing work in DH and who are working on women and people of color.

Time will tell if this is going to work or not, and how all of this gets implemented. But it’s better to think about it from the beginning than retrofit things as we go, inasmuch as that’s a possibility. As always, I welcome thoughts and input on anything I may have overlooked.