When I was at ASECS 2024, I got a question after my presentation about how I was organizing my data. I was thinking he meant how I was setting everything up overall, for example what schema I was going to use, and I sort of only half answered him because I don’t entirely know what I’m doing for the overall project. I have realized, however, that I complicated the question far more than it required. I also realized that wasn’t something I’d talked about here, and it likely should have been. I feel very strongly that transparency in what and how and why is important — a belief that was strengthened after a really strong presentation from the great scholars behind the Women’s Print History Project about the need for DH documentation that discusses the “why” as well as the “how.”

As I’ve mentioned before, this is a project with multiple phases. Phase One involved using OCLC Worldcat and the ESTC to locate individual copies and possibly previously missed or spurious publication information. I started with the excellent list of Lennox publications in Charlotte Lennox: An Independent Mind by Susan Carlile, which gave me a huge headstart. That’s where the maps on this site came from — an early effort to identify locations and see where clusters of copies might have been located. The limitations of Google Maps, though, specifically in the number of points per map, made this of limited usefulness. I may yet go back and try to dump all of it into something like Tableau and get a master map, but I haven’t yet. Probably not until I’ve finished cleaning up the data set.

There was then an interim stage I consider Phase 1.5, in which I took the data out of Google Maps and put it into an Excel spreadsheet. The data as it stood was in the following categories:

- ID #: this helped differentiate records so I could move them into a relational database eventually

- Longitude: location info courtesy Google Maps

- Latitude: location info courtesy Google Maps

- Library Name: the name of the library with the holdings (preferably not just the special collections dept)

- Description: intended to describe something about the book, such as edition # or suspected piracy, not the library

- Affiliation: what institution is the library affiliated with, if any

- Designation:(what sort of library/institution is it — this is the muddiest category because sometimes it refers to the library (unaffiliated) and sometimes to the institution (affiliated)

- Pub Year: publication year

- Location: where was the book published

- Bookseller: who was the bookseller/publisher

- Title: Title of the book/periodical

Now, as to why I chose to keep track of all this stuff, particularly about the institutions, part of it was because I thought it would be interesting to track this and see how the spread went. Part of it was because I thought it would help me track down funding to visit collections. And the last part of it, I think, is because I didn’t want to go back and add it in later in case I regretted not having it to begin with. It’s easier to cut info than to go back and add it in across all the records.

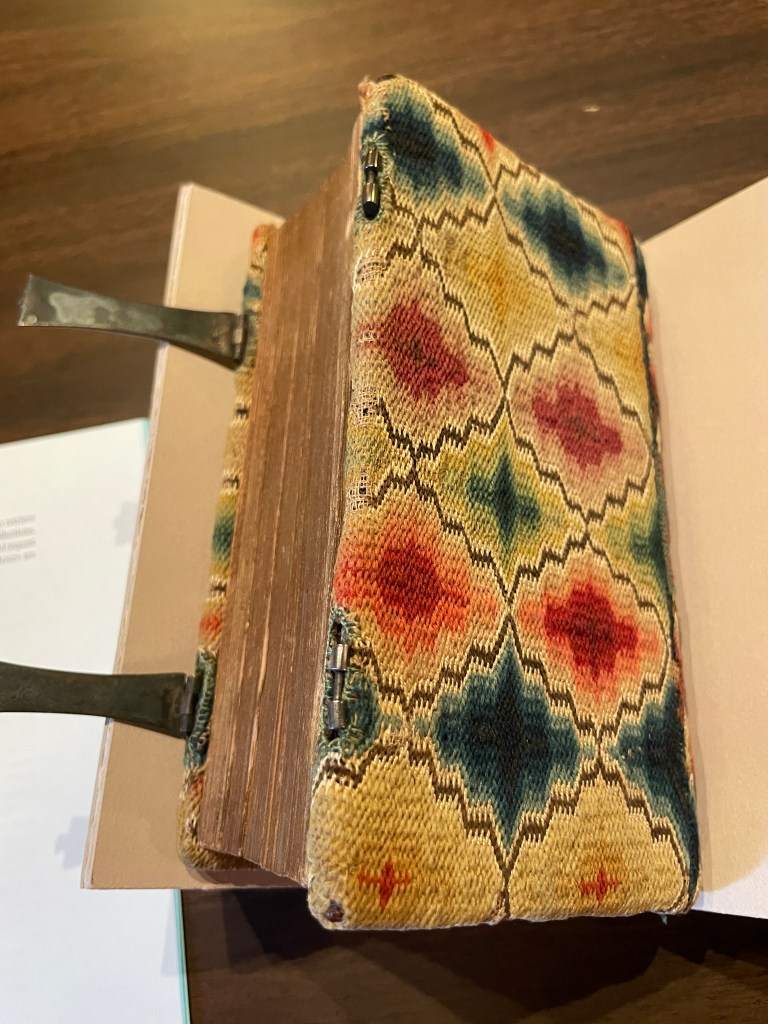

I’ve held to that philosophy as I’ve gone — I’d rather get all the information plus some and end up with something unnecessary than I would want to record less than I’d end up wanting. There is absolutely a point of diminishing returns, here, naturally, but it’s balanced by the realization that, for most of these copies, I will get only one bite at the apple. If I miss something or realize later what I needed, I may be able to get it by asking the librarians, but I likely won’t get a second visit to see it for myself. This is one reason that my local copies are my test cases, to ensure what information I’m recording and why before I start trying to build my photo album of all the special collections rooms I get to visit.

I hope this proves helpful to someone — I’m happy to provide more information or answer questions as needed. I’ll move toward describing Phase Two in an upcoming post.